One of the quickest and most sure-fi re ways to wreck an engine is to run it without oil, because even a smooth or polished surface has minute imperfections called asperites. These jagged spikes and ridges may only be a millionth of an inch high, but as metal moves against metal, the asperites on one surface collide and interlock with those on the other, and then have to bend or break in order to allow the movement to continue.

The cumulative effect of repeatedly bending or breaking thousands of asperites soon produces visible damage to the surface, known as wear. The effort expended in doing so is friction.

Each collision also generates heat, with local temperatures sometimes rising to as much as 1,600° C – enough, in severe cases, to weld the surfaces together.

Oil solves the problem by separating the two metal surfaces with a thin layer of fl uid, and fi lling the tiny valleys between the asperites: reducing wear, allowing moving parts to move more freely, and stopping them from welding themselves together.

Cleans, cools and protects

Lubrication is undoubtedly the oil’s main job, but it has a number of subsidiary functions. These were neatly summed up by one of the oil companies whose advertising slogan, at one time, was ‘cleans, cools and protects’.

- It cleans the engine by fl ushing away tiny particles of carbon or metal, and neutralising the acids produced from burning fuel.

- It cools the engine by carrying heat away from hot spots that can’t be reached by the engine’s water cooling system, such as the pistons and main bearings.

- It protects the engine by covering the metal parts to exclude air and moisture that would otherwise cause corrosion.

One signifi cant job that the advertising agency forgot is that oil also helps to create a gas-tight seal between – for instance – the piston rings and the cylinder walls.

Pressurised oil systems

A few very simple engines have no oil system at all. Two-stroke petrol engines, for instance, run on a mixture of oil and petrol, and rely on the engine’s demand for air to pull the petrol-oil mixture through the areas where oil is needed. Some small four-stroke engines rely exclusively on ‘splash-feed’ lubrication, in which a spike or paddle, protruding from the bottom of the con rod, flings oil around the inside of the crankcase, the bottom of the cylinder, and the underside of the piston.

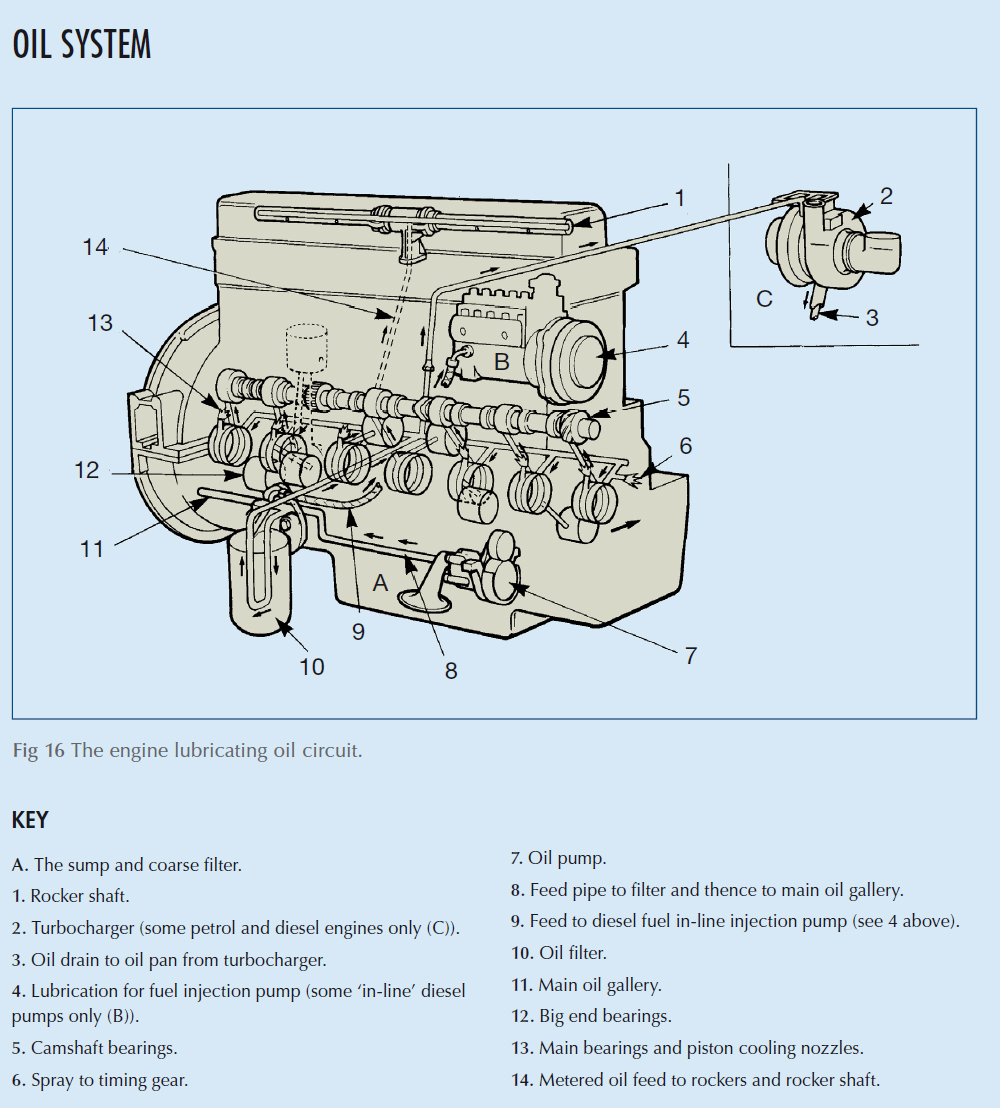

You don’t have to move far up the scale, though, to reach engines in which pressurised oil systems are standard. They use an oil pump to lift oil out of the sump and through a filter, before pushing it through a maze of oilways to the crankshaft, camshaft and rocker bearings; to the con rods and pistons; and out to ancillaries such as the turbocharger and fuel pump. Gravity then returns the ‘used’ oil to the sump.

Most of the lubrication system – like the pistons and main bearings that it serves – are deep inside the engine, and out of reach of a limited onboard tool kit. User maintenance is confined to making sure that the engine has a good supply of clean oil by topping up and changing the oil at regular intervals, and changing the filter.

In the longer term, it is a good idea to keep an eye on the oil pressure gauge. Some internal wear is inevitable, so as time goes by, the gaps between some of the moving parts will increase, making it easier for oil to seep away. This doesn’t just mean that the lubrication around the affected part will be less effective: it also means that less oil will reach other components, leaving you with an escalating trail of damage throughout the entire engine.

Oil grades and classes

It is pretty obvious that if the oil is to do its job of separating two moving parts, there has to be a gap between them that the oil can fill. This, however, means that if the oil were perfectly fluid it would simply escape through the gap, so to be effective an oil needs a certain viscosity, or ‘thickness’.

This seems to imply that a ‘thick’, viscous oil is better than a ‘thin’ one, but that is certainly not the case: viscosity is an indication of the friction between the molecules of the oil itself, so a very viscous oil makes starting difficult, wastes power and generates extra heat.

In other words, you need to choose an oil of the right viscosity for your engine.

There are lots of different ways of measuring viscosity but, to make life relatively simple, oils are now graded according to a system of numbers devised by the American Society of Automotive Engineers, in which the higher the number, the thicker the oil. Your engine manual may specify, for instance, that it needs an oil grade ‘SAE 40’.

The picture is made slightly more complicated by the fact that oils become less viscous as they warm up, so an oil that is right at normal operating temperature may be very much too thick for easy starting in the depths of winter. To overcome this, it was once common practice to use a much ‘lighter’ oil in winter, and to accept increased wear as a penalty that had to be paid. SAE catered for this by introducing a second series of ‘Winter’ grades, such as SAE 10W.

Oil technology has advanced enormously since the SAE grades were introduced. Now, additives mixed with the oil make it much less susceptible to changes in temperature. This means that most modern engine oils can be used in summer and winter alike, and therefore have summer and winter SAE grades shown together, such as SAE 20W/50 or SAE 15W/40.

Even ‘ordinary’ engine oils nowadays contain a cocktail of other additives intended to enhance particular aspects of their performance. Inevitably this means that some oils are ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than others, so various bodies have introduced performance standards to identify oils that are suitable for particular jobs.

The most widespread of these classification systems was developed by the American Petroleum Institute (API), which assesses an oil’s performance in each of two categories: S, for spark ignition (petrol) engines; and C, for compression ignition (diesel) engines. As time has gone by, the capabilities of the oil producers and the demands of the engine manufacturers have increased, so now there are a range of API classifications from SA/CA (the oldest and obsolete) up to SN and CK.

Most oils now meet SJ/CH or SK/CI specifications, and are perfectly suitable for use in most engines, but if you are faced with an unfamiliar brand it’s as well to check the quality designators printed on the can and to check, if necessary, that it is specified as suitable for a turbocharged engine.

... Things to do

SAFETY FIRST

The additives that make modern oils better for your engine make them worse for you. Take care to avoid unnecessary or prolonged contact with engine oil – new or used.

1. OIL LEVEL

Check the oil level each day that the engine is to be used. It is quite normal for an engine to ‘use’ a certain amount of oil.

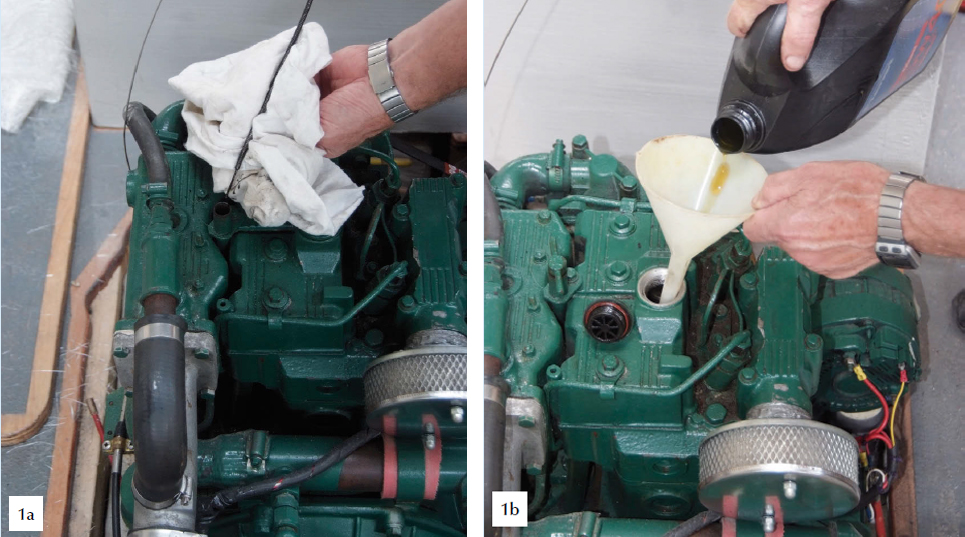

- a. Withdraw the dipstick, wipe it with a dry rag and then put it back, making sure it is pushed fully home. Pull it out again, and look at the oil level, which should be between the ‘max’ and ‘min’ marks. Then replace the dipstick.

- b. If necessary, top up the oil by pouring oil in through the filler cap – usually located on top of the rocker cover. Leave the engine for a few seconds for the new oil to drain down before re-checking the level.

2. CHANGING THE OIL FILTER

The oil and filter should be changed at the end of each season, or after about 200 hours’ use.

First run the engine up to operating temperature, then protect the area around the filter from spillages. Try to avoid contact with the used oil.

- a. ‘Spin-on’ filters are best removed by unscrewing with a strap or chain wrench.

- b. If that isn’t available or doesn’t work, drive a large screwdriver through the canister, just offcentre, and use it as a lever.

- f. Make sure the old rubber sealing ring isn’t stuck to the filter head, and replace it with the new one supplied with the filter.

- g. Replace the complete assembly, making sure the filter canister is correctly seated, and tighten the retaining bolt.

- h. Change the oil, then run the engine at tick-over for a few minutes to inspect for leaks around the filter. Even if no leaks appear, check the oil level and top it up, because some oil will be retained in the filter.

3. CHANGING ENGINE OIL

There’s no point changing the filter without changing the oil, and if your engine has a sump pump, this is a simple matter of pumping the oil into a suitable container. If not, you will have to resort to other methods:

- a. You will have to insert a small tube down the dipstick hole, connected to a pump, to suck the oil out.

- b. Top up with the right grade and quantity of oil.

References

Adlard Coles Book of Diesel Engines